The detective story seems predicated on action. Even the most leisurely or snobbish mystery novels contain some semblance of motion, and typically it is the primary detective who does most of the legwork. Of course, the level of sweat is based on who is writing the story. The British school of mystery writing, especially during its supposed “Golden Age” between the two world wars, places a greater emphasis on logic, deduction, and the puzzling nature of its central crime (which is almost always murder). The best examples of this style are any one of Dame Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple mysteries, plus for those interested in the subject, Dorothy L. Sayers and her insufferable aristocrat Lord Peter Wimsey offer up yet another view into the peculiar world of the “cozy” mystery.

The detective story seems predicated on action. Even the most leisurely or snobbish mystery novels contain some semblance of motion, and typically it is the primary detective who does most of the legwork. Of course, the level of sweat is based on who is writing the story. The British school of mystery writing, especially during its supposed “Golden Age” between the two world wars, places a greater emphasis on logic, deduction, and the puzzling nature of its central crime (which is almost always murder). The best examples of this style are any one of Dame Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple mysteries, plus for those interested in the subject, Dorothy L. Sayers and her insufferable aristocrat Lord Peter Wimsey offer up yet another view into the peculiar world of the “cozy” mystery.

As a reaction to this school of mystery writing, American authors working in the pulp market during this time developed a more brutal, less intellectual style of mystery writing. Later termed “hard-boiled,” this school puts a premium on action and violence, not dazzling displays of mental gymnastics. The foremost masters in this line are the trinity of Dashiell Hammett (who had been a real-life private eye for the Pinkertons before taking up the typewriter), Raymond Chandler, and the often overlooked Ross Macdonald. For his part, Mr. Hammett, who first started publishing his hard-hitting Continental Op stories in the early 1920s,“took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it in the alley.” These are the words of Raymond Chandler, who, in his 1944 essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” took to task the “Golden Age” mystery and instead upheld the more realistic and deeply cynical “hard-boiled” novel. In the groundbreaking essay, Mr. Chandler holds special venom for two things: 1) A.A. Milne’s novel The Red House Mystery, and 2) those American writers who wrote in the British vein. For the latter, Mr. Chandler concludes that American detective fiction is the “Junior Varsity” to its British seniors, and to make matters worse, the American detective novel about “pseudo-gentility” is far inferior to even to the most foppish British mystery.

Mr. Chandler’s thoughts on Rex Stout are hard to come by, but then again the usually tetchy Mr. Chandler probably would have found things to loathe about Mr. Stout’s Nero Wolfe mysteries. Beginning with 1934’s Fer-de-Lance, Mr. Stout would go on to write an astonishing thirty-three novels between 1934 and 1975. That is quite the accomplishment, especially since Wolfe, the series’s namesake, rarely leaves his brownstone apartment and has all the eccentricities of a “Golden Age” British detective. Built like a whale, Wolfe, a Montenegrin by birth but a naturalized American citizen, is a private detective with peculiar habits. First of all, as he says with trademark restraint in Before I Die, “I rarely leave my house. I do like it here.” Wolfe, like Jacques Futurelle’s little-known “Thinking Machine” Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen, is an all-consuming mind that almost never shows traces of being wrong or mislead. On top of that, Wolfe is also an all-consuming belly, and every single one of Mr. Stout’s novels contain detailed examinations of Wolfe’s fussy eating habits, from his preference for unopened beer bottles to his profound appreciation for shad roe.

While this may sound Proustian, Mr. Stout managed to keep his character from sounding too self-absorbed, despite his diva-esque dietary demands. Besides, as Criminal Element writer Robert Hughes points out, “It’s Archie [Nero’s airy and streetwise sidekick and the narrator of the series] we want to read.” Wolfe is but one piece of a larger household. Besides Wolfe and Archie there is Fritz Brenner, Wolfe’s Swiss butler and exceptional cook, and Theodore Horstmann, the sometimes volatile florist who helps Wolfe to maintain his vast collection of orchids. The wonderful dynamics of this household often overshadow the cases in each novel, and throughout the entire length of the series, Mr. Stout highlighted the wonderful nature of domestic life in a way akin to Hergé, the creator of the popular character Tintin. As Peter Strzelecki Rieth says in his masterful “Tintin: The True European”: “Towards the end of his life, Tintin focused more and more on the truly amazing nature of domestic life and the specific adventure of human interaction, with all its nuance and humor.” The very same could be said for the Nero Wolfe mysteries, which read more like P.G. Wodehouse than James M. Cain or any one of Mr. Stout’s American counterparts.

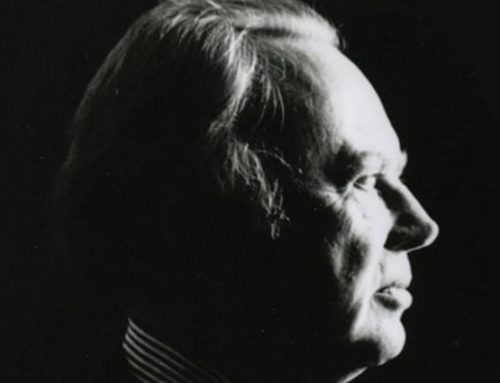

Much of the charm of these novels is the result of Mr. Stout’s craftsmanship. Always readable, his novels bristle with sharp dialogue and a leisurely view of life. Finding these qualities in a mystery novel, which are usually about death and crime after all, might seem on the surface sardonic, but Mr. Stout’s Nero Wolfe mysteries never come across as bitter or otherwise ill-tempered. Born to Quaker parents in Noblesville, Indiana, Mr. Stout spent his formative years in Kansas – the very last place you’d expect find a cosmopolitan.

Encouraged by his religious parents (especially his teacher father), Mr. Stout showed an early aptitude for scholarship. A math prodigy who won a spelling bee at thirteen and graduated from high school at sixteen, he came into young adulthood with a range of options ahead of him. At first, Mr. Stout choose the road to academia, but after briefly attending the University of Kansas, he dropped out in order to enlist in the US Navy. From 1906 until 1908, Mr. Stout served in the Navy as a yeoman, and according to The Wolfe Pack website, served aboard President Theodore Roosevelt’s official yacht as a warrant officer.

After his discharge, Mr. Stout worked a variety of odd jobs all the while writing copious amounts of poems, short stories, and articles. Then, sometime around 1916, he and his brother Robert created and implemented a school banking system that allowed students to keep track of their money in saved accounts. This venture, which was soon adopted by hundreds of schools, made Mr. Stout independently wealthy. For a time, Mr. Stout lived in Paris and traveled widely in Europe. While there, he began to develop his skills as a writer, and after starting out in the ubiquitous pulp magazines of the day, he turned to novel writing. His first efforts were primarily “literary” novels that dealt heavily with psychology. Later, Mr. Stout tried writing science fiction and even a political thriller: 1934’s The President Vanishes.

Soon thereafter, after the success of Fer-de-Lance, Mr. Stout would focus predominately on detective fiction, even though he abandoned the genre from time to time. All the while managing to churn out a Nero Wolfe novel almost yearly, he actively engaged in politics. Although he helped to start the radical and socialist magazine The New Masses, he soon abandoned the project due to the editorial policy of staunch Communism. Still, despite his stance against The New Masses, Mr. Stout, who would later tell the Washington Times-Herald that he was “pro-Labor, pro-New Deal, pro-Roosevelt left liberal,” remained active in leftist publishing circles throughout a large portion of his early career. Mr. Stout was once one of the directors of the left-wing Vanguard Press, and around the same time he became an early board member of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Despite his clear allegiance to progressive causes, Mr. Stout remained throughout his life an ardent anti-Communist. During the World War II, he wrote anti-Nazi propaganda as a member of the War Writers’ Board and wrote even more vitriolic anti-Nazi pieces for the New York Times. After the war, Mr. Stout’s close ties to the left landed him in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Accused of being a Communist sympathizer by Martin Dies, Mr. Stout shot back by pronouncing: “I hate Communism as much as you do…but there’s one difference between us. I know what a Communist is and you don’t.” By the 1960s and 1970s, Mr. Stout was alienating readers with his hawkish stance on the Vietnam War, which is most on display in his final novel, A Family Affair.

All in all, Mr. Stout’s life was as interesting, if not more so than the lives of his characters. Like Wolfe, he was a well-traveled personage who knew well the intellectual and well-heeled sets of his time. This knowledge helped Mr. Stout greatly, for even during the grimness of the Great Depression, Wolfe’s novels inevitably focus on white-collar lives, from college professors to the landed rich in New York’s Westchester County. Beyond this, Wolfe’s brownstone apartment in the city seems like a comfortably contained world for many readers, and this type of escapism is an escapism that retreats (or returns) to the home. In the larger picture, this is completely atypical for American detective fiction, especially the “hard-boiled” variety. While his peers were rewriting the myth of the lone Western gunslinger for the urban twentieth century, Mr. Stout was essentially Americanizing the British model without losing any of the particulars. Therefore, one could call Mr. Stout a bridge between the two schools (for his part, Archie at times likes to fashion himself as a tougher, less pampered investigator than Wolfe), but such grand designs miss the most important thing about the Nero Wolfe mysteries.

All in all, Mr. Stout’s life was as interesting, if not more so than the lives of his characters. Like Wolfe, he was a well-traveled personage who knew well the intellectual and well-heeled sets of his time. This knowledge helped Mr. Stout greatly, for even during the grimness of the Great Depression, Wolfe’s novels inevitably focus on white-collar lives, from college professors to the landed rich in New York’s Westchester County. Beyond this, Wolfe’s brownstone apartment in the city seems like a comfortably contained world for many readers, and this type of escapism is an escapism that retreats (or returns) to the home. In the larger picture, this is completely atypical for American detective fiction, especially the “hard-boiled” variety. While his peers were rewriting the myth of the lone Western gunslinger for the urban twentieth century, Mr. Stout was essentially Americanizing the British model without losing any of the particulars. Therefore, one could call Mr. Stout a bridge between the two schools (for his part, Archie at times likes to fashion himself as a tougher, less pampered investigator than Wolfe), but such grand designs miss the most important thing about the Nero Wolfe mysteries.

Comfortable because of the eccentricities and exotic because of its domesticity, the Nero Wolfe novels offer up a singular world of essentially bloodless crime and impeccable certainty. While Archie and Wolfe do not escape each novel unscathed, every reader knows how each novel will end. This is easy escapism, but not mindless nor useless. Besides, as Mr. Chandler himself says in The Simple Art of Murder,“all reading for pleasure is escape, whether it be Greek, mathematics, astronomy, Benedetto Croce, or The Diary of the Forgotten Man.” Therefore, despite their surface-level whimsy, the Nero Wolfe novels teach us a lot about the value of friendship and the importance of daily rituals. More importantly, the Nero Wolfe novels elevate the home to center of life, and that is something too often overlooked by more “literary” novels.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Oh what fun! Many thanks!

Literary criticism from Phyllis McGinley: “Come mark them up with a big, black zero/ Who don’t love Archie, Rex, and Nero.”

Should have been “mark them down.”

I was introduced to Rex Stout by the elderly lady who ran a used bookstore just up the street from my apartment in Stillwater, OK during my college years. That was 40 years ago, and Wolfe’s brownstone still is one of my favorite escapes. The novels lack the plot intricacies of Christie, but the draw is the time spent with Wolfe’s “family”. Archie, Fritz, Saul, Fred, Theodore, Inspector Cramer, Sargeant Stebbins, Lieutenant Rowcliff, and Wolfe make me feel at home whenever I read or listen to Stout’s works. Thank you for the article.

If you’re wondering what was Raymond Chandler’s view of Nero Wolfe, look no farther than the first few pages of his first novel. Chandler wasted absolutely no time in making this clear, as he introduces General Sternwood in his orchid room:

“The air was…larded with the cloying smell of tropical orchids in bloom.”

“The plants filled the place, a forest of them, with nasty, meaty leaves and stalks like the newly-washed fingers of dead men. They smelled as overpowering as boiling alcohol under a blanket.”

“Do you like orchids?”

“Not particularly”, I said. The general half closed his eyes.

“They are nasty things. Their flesh is too much like the flesh of men. And their perfume has the rotten sweetness of a prostitute.”

I love Chandler. And I love Wolfe, and Archie, and the shad roe and the beer bottles…but I think it’s safe to say that Chandler did not 😉