If we are indeed witnessing the nadir of American politics—or at least its accelerating decline—we should listen closely to Augustine. The “Augustine Option,” meaning a life lived in the final years of Rome, can offer key insights into how we should understand and address these tumultuous times.

To the continued debate over whether religious Americans should pursue a Benedict or Dominic option, I propose adding a third historic churchman to the mix: Saint Augustine. This is not because I have some alternative Augustinian vision for shaping the future of Christianity in the West (though perhaps some scholar of Augustine should propose one!). Indeed, I’m not the first to suggest an “Augustine Option”—that honor goes to the Catholic archbishop of Philadelphia Charles Chaput. Rather, I would offer that the complexities and paradoxes of Augustine and his writings contain much that would benefit our current political and cultural distemper. America would do well to return to his person and wisdom.

To the continued debate over whether religious Americans should pursue a Benedict or Dominic option, I propose adding a third historic churchman to the mix: Saint Augustine. This is not because I have some alternative Augustinian vision for shaping the future of Christianity in the West (though perhaps some scholar of Augustine should propose one!). Indeed, I’m not the first to suggest an “Augustine Option”—that honor goes to the Catholic archbishop of Philadelphia Charles Chaput. Rather, I would offer that the complexities and paradoxes of Augustine and his writings contain much that would benefit our current political and cultural distemper. America would do well to return to his person and wisdom.

Augustine speaks effectively to a broad diversity of audiences. He embodies both sophisticated urbanism and provincialism. An ethnic Berber born and raised in Numidia (modern-day Algeria), he spent much of his career in Milan among the elites of the late Roman Empire. He drank deeply from pagan literature and philosophy as a Manichean and Neo-Platonist, yet he became a Catholic. He was self-professedly African yet also thoroughly European. He came into the world in the waning years of the Roman Empire (354 A.D.), was one of the Church’s most respected and outspoken leaders when Rome was sacked by a mercenary Visigoth army (410 A.D.), and died as Vandal barbarians stormed Hippo, the seat of his episcopate (430 A.D.).

The diversity of his audience is also evident in the peculiar place he holds in Christian and Western self-identity. He is, of course, beloved by the Catholic Church, which not only annually celebrates his feast day, but routinely cites his theological writings to substantiate its doctrines. Indeed, there is even a Catholic religious order named after him, the Augustinians. Martin Luther, the lightning rod of the Reformation, was himself an Augustinian monk. This is perhaps why Augustine also looms large in Protestantism: Lutherans and Calvinists, among others, carefully study and appreciate his doctrine of grace and reflections on predestination. His artful Confessions, the first spiritual autobiography in Christian history, is beloved by Christians (and non-Christians) of all stripes. Even Jewish columnist David Brooks invokes Augustine.

Adherents of both the right and the left call Augustine a spiritual and intellectual mentor. Unsurprisingly, a wide diversity of conservatives—from Eric Voegelin to Michael Gerson, and even some libertarians—positively cite him. More interesting is the respect he’s earned from liberals, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Washington Post columnists E.J. Dionne and Elizabeth Bruenig. Bruenig’s connection to the theologian is especially interesting—she cites him as the preeminent influence on her decision to convert to Catholicism. Augustine’s thought is frequently audible in her editorial musings.

What, then, are the lessons that we can learn from Augustine in 2018? As hinted at above, he lived in disastrous times that overlap with our own, as he witnessed the erosion and then collapse of the late Roman Empire. He also encountered strong heretical movements in North Africa that threatened to tear the early Church apart. Augustine met both of these challenges head-on. After the pillaging of Rome, he penned the masterful City of God, which defended Christianity against pagan claims that the new religion was the reason for Rome’s fall. It also provided a religio-political vision that would prove foundational in the remaking of the West from Rome’s ashes. His writings and efforts against the Donatist heretics—who taught that clergy must be faultless for the sacraments to be valid—proved fundamental in reversing their influence. In the face of every challenge, Augustine offered no retreat, and indeed was often on the offensive. This included in his own personal life, where he overcame his sexual demons. From a man who earlier in life asked God to grant him chastity but “not yet,” he is famous for his latter years of diligent purity, a model quite appropriate for clergy in this time of scandal.

Though he was pugnacious, Augustine was ever the gentleman. This is evident in his correspondence with another larger-than-life Christian of the fifth century, Saint Jerome. The two sparred over numerous issues—Jerome’s plans to translate Scripture into Latin (what became the Vulgate), the contents of the Biblical canon, and Biblical interpretation, to name but a few. The often testy Jerome could be arrogant and aggressive in his responses to Augustine. He called Augustine a “youth in the field of scripture,” one so bold as to “challenge an old man,” and “seek[ing] a reputation for one’s own name by attacking illustrious persons.” Augustine never returned Jerome’s insults, instead praising his interlocutor and deferring to his authority. Would that we had more pundits who evinced such charity in our own day!

Augustine’s intellectual prowess was matched by his profound, intimate spirituality, which has led many to name him one of the greatest spiritual writers in Church history. His Confessions is perhaps the most personal, emotively charged spiritual reflection yet written in the Christian faith. The recounting of his spiritual journey has stood the test of time, converting (and re-converting) readers to Christianity for almost 1,500 years. Consider one of the more famous excerpts from the classic text:

Late have I loved you, beauty so old and so new: late have I loved you. And see, you were within and I was in the external world and sought you there, and in my unlovely state I plunged into those lovely created things which you made. You were with me, and I was not with you. The lovely things kept me far from you, though if they did not have their existence in you, they had no existence at all. You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, you put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath and now pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is yours.

These are the words of an expert contemplative, pushing theological reflection to the heights of spiritual ecstasy. One of the most memorized extra-biblical sentences in Christian thought is found at the beginning of Confessions, “Thou hast formed us for Thyself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in Thee.”

If we are indeed witnessing the nadir of American politics—or at least its accelerating decline—we should listen closely to Augustine. The “Augustine Option,” meaning a life lived in the final years of Rome, can offer key insights into how we should understand and address these tumultuous times. Just as Augustine remained deeply invested in the political and religious debates of his day—perceiving himself as both Roman and Christian—so should we “lean in” to the distemper of our day by remaining engaged, even if shouted down or ridiculed.

Augustine was also untiring in his commitment to his fellow citizens and Christians, exemplified in great acts of charity while bishop of Hippo. His biographer Possidius describes him as eating sparingly, working tirelessly, despising gossip, shunning temptations of the flesh, and exercising prudence in the financial stewardship of his see. Augustine picked many fights he thought worth the trouble, but he maintained humility and charity. Late in life he even penned a manuscript correcting errors in his earlier writings!

The man was brilliant—religious scholar Robert Louis Wilken has argued that Augustine was probably the most intelligent man in the late Roman Empire—yet he was also a contemplative and mystic. Strength and poise, charity and humility, contemplation and introspection: these are the traits of Saint Augustine, and these are what we may hope to attain if we thoughtfully consult him. Thus should we take same advice offered to an unconverted Augustine one day while he sat beneath a fig tree: “tolle lege”—“take up and read.”

Republished with gracious permission from the American Conservative (August 2018).

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

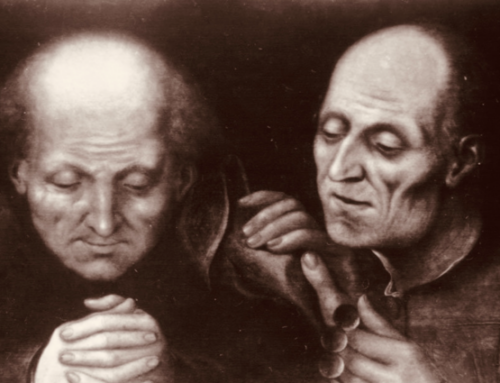

The featured image is “The Triumph of Saint Augustine” (1664) by Claudio Coello courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Leave A Comment