In Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Doulos, it is as if there is an existential darkness present throughout. In this world, no matter how cunning the schemes or how fail-safe the get-away plans are, for all concerned there is a retribution coming. In Melville’s cinematic universe the wages of sin are always death…

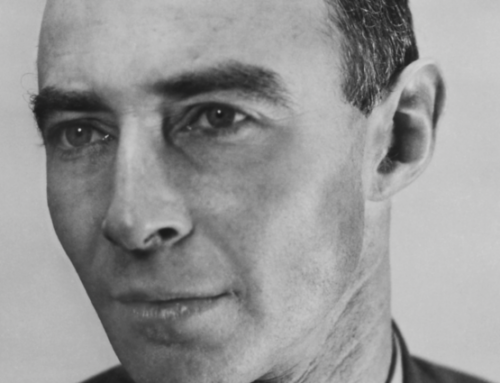

Recently, at London’s British Film Institute, a major retrospective was staged dedicated to the work of the director, Jean-Pierre Melville. For those unfamiliar with the films of the brilliant, if idiosyncratic, Frenchman—born 100 years ago this year—then Le Doulos, originally released in 1962, is a good place to discover his cinematic legacy.

Recently, at London’s British Film Institute, a major retrospective was staged dedicated to the work of the director, Jean-Pierre Melville. For those unfamiliar with the films of the brilliant, if idiosyncratic, Frenchman—born 100 years ago this year—then Le Doulos, originally released in 1962, is a good place to discover his cinematic legacy.

The moody gangster movies of Melville’s male-dominated world—women are rarely more than victims or adoring ornaments—are set in a twilight cityscape, filled with crime and its myriad consequences. Those cursed to walk its desolate streets are indeed haunted figures, and not just, it seems, by the forces of the law.

Le Doulos—loosely translated as ‘the informer’—is about two such men; it is classic Melville territory. The criminals are played by two greats of French Cinema, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Serge Reggiani. From the outset, one senses the despair around Faugel (Reggiani). He carries all the disappointment of a man caught in a netherworld of criminality and prison. Knowing that any escape from this world is impossible now, he has become ever more desperate and dangerous. His partner in crime is Silen (Belmondo). The looks and screen presence of Belmondo who is, by turns, both menacing and beguiling, both lover and psychopath, are perfect for the role of the younger, smarter man, still intent on getting out while he can. His optimism about the possibility of a new life free from crime appears misplaced, however, and stands in sharp contrast to the ease with which he continues to brutalize those around him. Furthermore, there is a sneaking suspicion that all may not be as it seems with this particular criminal.

From the start, one senses both men are doomed—a common Melville trope.

Their volatile alliance is a relationship that nervously alternates between loyalty and betrayal, greed and desire, revenge and murder. The plot is engrossing—any further elaboration would dent the pleasure of watching it unfold. Suffice to say, the tale twists and turns but never loses the audience. Like the dialogue, the dramatis personae are kept to a bare minimum; the unfolding story’s pace is perfectly pitched. Predictably, the cinematography is as downbeat and forlorn as the individuals on screen, with the empty Parisian streets reflecting the equally empty consciences of Faugel and Silen.

Melville was part of a cinematic New Wave that emerged in the 1950s and that eventually came to dominate French and indeed European cinema for decades after. From the late 1960s onwards, New Hollywood’s aesthetic space—as seen in such films as Bonnie and Clyde—was to be derived largely from this same movement. In Melville’s case, this is a curiously circular development as he had been first captivated by Old Hollywood while watching Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane at a London cinema when stationed there with the Free French Army during the Second World War. It is no exaggeration to say that cinematic experience changed the course of Melville’s life.

Although Melville’s career was never to bring him to the United States, he remained throughout his life a lover of all things American. Stories abound of the Stetson-wearing director, with music blaring, driving a Ford convertible too fast down Parisian boulevards. Despite his love of films, it is said that Melville hated the process of making them; and, perhaps inevitably, he fell out with most of those with whom he worked. But still, he worked. Le Doulos is part of a cycle of now legendary crime dramas—six in all—whose particular mix of 1960s Paris and 1940s Hollywood is a potent and never less than enthralling blend.

To some—at least at first glance—Melville’s films may appear to glamorize the Parisian underworld. It is true, as Le Doulos amply demonstrates, that the director produced stylish films chronicling that netherworld. Nevertheless, in the end, his cinematic gems stand like mirrors revealing the emptiness of the criminal underworld and the lives of those trapped in its ever-lengthening shadows.

This is film noir with an emphasis on ‘noir.’ Most of the scenes in Le Doulos seem to be set at night. That said the film’s lighting is about more than mood setting. It is as if there is an existential darkness present throughout. And with each passing scene, the darkness appears to expand further before, ultimately, eclipsing all within its reach.

In this world, no matter how cunning the schemes or how fail-safe the get-away plans are, for all concerned there is a retribution coming. In Melville’s cinematic universe the wages of sin are always death.

Republished with gracious permission from St. Austin Review.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Thanks for this. I’m really only familiar with his film Le Samourai (which I love), but now I want to explore more of his work.