By now, countless articles have been written on Brexit. But what implications does Brexit have for the United States? In answering this question, I do not want to focus on whether Brexit was a good idea or not. It’s far too soon to tell. Instead, I will consider whether the decision procedure for Brexit—the referendum—was sound.

By now, countless articles have been written on Brexit. But what implications does Brexit have for the United States? In answering this question, I do not want to focus on whether Brexit was a good idea or not. It’s far too soon to tell. Instead, I will consider whether the decision procedure for Brexit—the referendum—was sound.

The Washington Post published an essay about how, after the vote, millions of Britons were Googling the European Union to find out what it was. Vox ran an article titled “Regrexit” that told the stories of voters who voted Leave, but who regretted it immediately after. One would guess that voters acted without basic knowledge of the issues, and as if their actions didn’t matter. Given the importance of the issue, how could this be the case?

Imagine if I came up to you and told you I will soon force you to spend $30,000 on a new car of your choice. How would you react? Undoubtedly, you’d be irritated, perhaps even panicked, about having to make such a major purchase. But you would probably spend the remaining time trying to make the best of a bad situation: You’d compare models, features, reviews, etc. to make sure that you’d at least get your money’s worth.

Now let’s tweak the scenario slightly. I will still force you to spend $30,000 on a new car. But now there is only a one in 40,000,000 chance that you will get the car you choose. Otherwise, you will have one randomly assigned to you. Now how would you react? Suddenly going to the effort of getting that information doesn’t seem worthwhile, since the odds it will make a difference are practically zero. Even when you factor in the dollar value of picking a good car, since this outcome is so unlikely, the expected value of being a responsible car shopper is tiny.

The scenario above is basically a referendum, like Brexit. The voting pool is so large that no individual voter has any incentive to do all the things required to vote responsibly, since doing so is expensive (in terms of time and money), and there’s no personal cost to getting it wrong. If any voter had become an expert on the relationship between the UK and the EU in the weeks before the referendum, and poured his heart and soul into treating the issue with the seriousness it deserves, the result would still have been exactly the same.

Okay, but what does this have to do with the United States? In November, U.S. voters will face a similar choice: the exercise of power, decoupled from personal costs, and hence personal responsibility. The mess we are in, in terms of the sorry state of U.S. politics, has been a century-long experiment from unchaining power from accountability. At least when the U.S. was still genuinely federalist, and the majority of governance anybody cared about took place in City Hall or the State House; the small size of voting pools, combined with personal knowledge and reputation within communities, incentivized some small amount of civic virtue. Now, not so much.

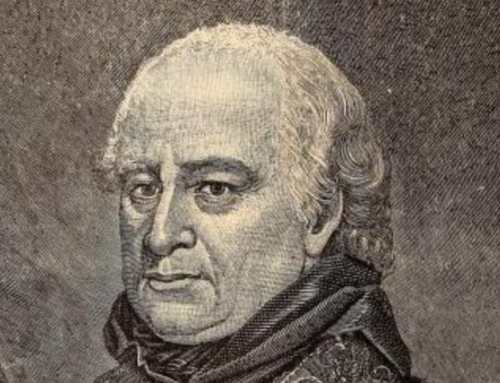

“Limits on democracy are un-American!” comes the reply. Not so. Consider what some of the Founders had to say on the subject.

Here’s James Madison: “Democracy is the most vile form of government…. Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property: and have in general been as short in their lives as the have been violent in their deaths.”

Alexander Hamilton: “We are a Republic. Real Liberty is never found in despotism or in the extremes of Democracy.”

John Adams: “Democracy will soon degenerate into an anarchy; such an anarchy that every man will do what is right in his own eyes and no man’s life or property or reputation or liberty will be secure, and every one of these will soon mould itself into a system of subordination of all the moral virtues and intellectual abilities, all the powers of wealth, beauty, wit, and science, to the wanton pleasures, the capricious will, and the execrable [abominable] cruelty of one or a very few.”

Even Thomas Jefferson, one of the most populist Founders, feared democracy: “Democracy is nothing more than mob rule, where fifty-one percent of the people may take away the rights of the other forty-nine percent.”

The lesson that Brexit has to teach the U.S. is one we knew in 1787, but seemed to have forgotten: democracy is a means, not an end in itself. To the extent that it produces good governance, we should embrace it. To the extent that it does not, we should avoid it. The whole point of our Constitutionalized compound republic is using elections as one tool among many to control those who would exercise power over us.

It’s probably too late to avoid the consequences of unrestrained democracy in 2016. Let’s hope we wise up before too long.

Books on the topic of this essay may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore.

Every concerned American therefore should read Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America.”