“There are two or three different people in every man’s skin. Who shall draw a line and say here genius ends and madness begins?” —Clara Morris, actress and friend of John Wilkes Booth

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., is one of the most dramatic and famous events of American history. Yet beyond the familiar, basic facts of the story, there are many fascinating details relating to John Wilkes Booth’s conspiracy, the execution of his plot, and its aftermath of which most Americans are unaware. Here are ten little-known aspects of the Lincoln assassination:

10. John Wilkes Booth and his brothers appeared in a production of Julius Caesar less than six months before the assassination

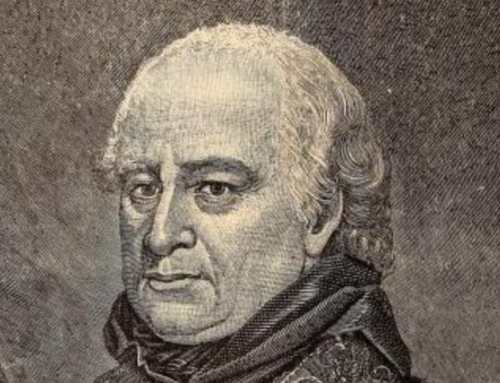

John Wilkes and his older brothers, Edwin and Junius Brutus, Jr., followed their famous father into the world of acting. Edwin was the greatest thespian of the trio, exceeding even the fame of his successful father. Whereas Booth père was histrionic on stage and unstable off it (being a conspicuous alcoholic), Edwin was renowned for his understated, realistic public portrayals and his gentleness of manner in private. John Wilkes was, in contrast, temperamental, and a mediocre actor, who was known more for his physical acting—he more than once received real wounds while participating in on-stage fights—and his superior good looks. On November 25, 1864, less than six months before the assassination, the three Booth fils appeared in a benefit performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theater in New York. Proceeds from the performance went to the creation of a statue of William Shakespeare that still stands in Central Park. John played Mark Antony, Edwin portrayed Brutus, and Junius was Cassius.

9. Booth’s plot included the killing of other members of the Lincoln Administration

Often forgotten is that John Wilkes Booth planned not only to kill Lincoln by his own hand, but to have his cohorts kill Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward, thereby decapitating the United States government and throwing it into confusion. Unfortunately for Booth, German immigrant George Atzerodt—charged with murdering Johnson—lost his nerve and got drunk, while Lewis Powell succeeded only in severely injuring Seward, who was already bed-ridden from a carriage accident, stabbing him multiple times in the upper body and face. Powell (whose alias was Lewis Payne, or Paine) was a young, hulking ex-Confederate soldier who had served as one of the famous Mosby’s Rangers. Only twenty-one years old at this death, he was one of the four conspirators executed by order of the the military tribunal that tried the case.

8. Booth carefully chose the venue of Ford’s Theater as the perfect stage on which to star in the most dramatic assassination of all-time

John Wilkes Booth was no madman. He was a well-liked and well-known actor, considered by many women to be one of the handsomest men in America, whose devotion to the Confederate cause and hatred of Abraham Lincoln grew as the prospects of the former dimmed and the renown of the latter increased. “Our country owed all her troubles to him,” Booth wrote in his diary after the assassination, “and God simply made me the instrument of his punishment.” A familiar presence at John T. Ford’s Washington theater, he moved easily around the building on the day of the assassination, preparing for his greatest role, as a real-life Brutus exacting revenge on a tyrant who had destroyed liberty. The conductor of the Ford’s Theater orchestra would later claim to have overheard Booth proclaim during the play’s intermission, prior to the assassination, “When I leave the stage for good, I will be the most talked about man in America.” After committing the deed, Booth leapt out of the president’s box to the stage below, holding up the bloody knife he had used to stab Major Henry Rathbone, who had tried to apprehend the assassin, and shouting in supremely dramatic fashion, “Sic Semper Tyrannis! The South is avenged!”

7. Alleged conspirator Mary Surratt was the first woman executed by the United States government

Mary Surratt operated a boardinghouse in Washington, D.C., that served as a meeting place for Booth for his co-conspirators. She vehemently maintained her innocence after her arrest, despite some damning—and later, controversial— evidence presented at her trial by the military tribunal. Many observers expected her to receive merely a prison sentence, but she was condemned to be hanged alongside Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Five members of the military tribunal petitioned President Andrew Johnson to spare Mrs. Surratt’s life, but Johnson later claimed never to have seen the clemency request. Some researchers have suggested that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who wished to exact revenge for Lincoln’s murder, intercepted the petition. At the time, however, many claimed that it was the military tribunal’s prosecutor, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of the U.S. Army, who suppressed the petition. Holt tried to clear his name for eight years after the trial, producing in 1873 a series of statements from witnesses who claimed that Johnson had indeed seen and considered the clemency petition, but that the Tennessean refused to commute Mrs. Surratt’s death sentence. One witness reported that Johnson averred that it was she who “kept the nest that hatched the egg” of the assassination plot and that he believed that showing lenience to Mrs. Surratt on account of her sex “would license female crime.”

The Surratt family were devout Roman Catholics, a fact that may have made her execution more palatable to largely anti-Catholic, Protestant America. Certainly some writers in the wake of her hanging even pointed to her Catholicism as proof of a wider “papist” conspiracy to kill Lincoln. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, most Americans had come to consider Mrs. Surratt wrongly convicted; most historians today side with the military tribunal in finding her guilty. Whatever the truth about her culpability, today her restless spirit is said to haunt her home in Surrattsville (now Clinton), Maryland.

6. John Surratt, who conspired with Booth, escaped punishment for his involvement in the plot

Mary Surratt’s son, John, was a Confederate agent (as Booth himself perhaps was) and surely the conspirator closest to the ringleader-actor. But Surratt was in New York the night of April 14, and after news of the assassination reached him, he fled first for Canada, where a Catholic priest gave him refuge. Under an assumed name, he soon made his way to Europe, enlisting in the Papal Guard in Rome. Eventually identified and captured by American authorities, he was returned to the United States for a civilian trial in Washington, D.C. The jury deadlocked, and Surratt was set free in November 1868. Two years later, he embarked on a public lecture tour, detailing his role in Booth’s early scheme to kidnap Lincoln while denying knowledge of the assassination plot. After one successful lecture, however, public uproar caused Surratt to cancel a second talk, and he never spoke publicly again about his association with Booth. Surratt died in 1916 at the age of seventy-two.

5. The $100,000 reward for the capture of Booth and his co-conspirators was divided among thirty-four men

Five days after the assassination, Secretary of War Stanton oversaw the creation of a unprecedented wanted poster offering $50,000 for the capture of Booth, and $25,000 each for the apprehension of John Surratt and David Herold. Surratt escaped, but Booth and Herold were eventually hunted down by detectives and members of the Sixteenth New York Cavalry. Hundreds of people filed claims for the reward money, however, and there was much acrimony about how to divide up the $75,000. In the end, Congress awarded $15,000 to detective Everton Conger, $5,250 to Lieutenant Edward Doherty, $3,750 to investigator Lafayette Baker, $3,000 to Baker’s cousin, detective Luther Byron Baker, and $1,654 to each of the twenty-six cavalrymen. The remaining $5,000 was split among four other investigators.

4. Major Henry Rathbone, who shared the box with the Lincolns at Ford’s Theater, later killed his wife

General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife were the original choices to join the Lincolns in the president’s box at Ford’s Theater on the evening of Good Friday, April 14. But the Grants demurred, and Mary Todd Lincoln instead invited Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, to watch the comic play, Our American Cousin, with her and the president. After Booth shot Lincoln, Rathbone rose from his chair and tried to grab the assassin, but Booth stabbed Rathbone in the arm, slicing his flesh to the bone. Rathbone bled profusely, and was only tended to belatedly by doctors, so intent were they on the president’s dire condition. Rathbone never forgave himself for failing to prevent the assassination, and he became increasingly unstable in later years, after marrying Clara and fathering three children with her. Living in Germany in 1883, one night he threatened the children and then attacked Clara, shooting and stabbing her to death. Found to be criminally insane, the German court confined him to an asylum for the rest of his life.

3. Booth kept a diary while on the run after the assassination, and some of its pages are missing

Booth’s was not a suicide mission; rather, he had devised an escape plan whereby he would make his way out of Washington, D.C., across the Potomac River into Virginia, into what he assumed would be the welcoming arms of his Southern compatriots. Accompanied by David Herold, Booth was on the run for twelve days, stopping in southern Maryland at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who tended to Booth’s ankle, which the actor had broken either in his leap from the president’s box at Ford’s Theater or when his horse slipped and fell on him during his getaway. During this time, Booth kept a diary, in which he justified his actions, first in plotting to kidnap, and then to kill, Lincoln:

For six months we had worked to capture, but our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done…. With every man’s hand against me, I am here in despair. And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for. What made Tell a hero? And yet I, for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew, am looked upon as a common cutthroat. My action was purer than either of theirs. One hoped to be great himself. The other had not only his country’s but his own, wrongs to avenge. I hoped for no gain. I knew no private wrong. I struck for my country and that alone.

Though this diary was taken off Booth’s body by the men who captured him in a Virginia barn, it was suppressed by Edwin M. Stanton’s War Department and never presented at the trial of the conspirators. When its existence came to light two years later, during the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson, several of its pages were missing, a fact that fed far-fetched theories that Booth had implicated members of the Lincoln Administration in the assassination plot, perhaps even Stanton himself. For what it’s worth, Lafayette Baker, one of the men who apprehended Booth, swore that Booth’s diary was intact upon his capture.

2. Boston Corbett, the man who killed Booth, had castrated himself because of his religious fanaticism

Sergeant Boston Corbett was a member of the Sixteenth New York Cavalry regiment that hunted Booth down at the Virginia farm of Richard Garrett in the early morning hours of April 26. The Union horse soldiers surrounded and set fire to the barn in which Booth and his accomplice David Herold were holed up in an attempt to flush the men out. Corbett peeked through a crack in the wall of the barn and, fearing that Booth would discharge his carbine rifle at the soldiers or perhaps escape, fired his Colt revolver at Booth. The bullet entered Booth’s neck, severing his spine and paralyzing him instantly. Corbett won acclaim for his deed among the northern populace, but he was ill-suited to be the avenging hero of the republic. Mentally unbalanced—perhaps as a result of mercury exposure, a consequence of his on-and-off trade as a hat-maker—Corbett was a religious fanatic who had castrated himself at the age of twenty-six as a way to ward off sexual temptation. In the years after his killing of Booth, he became ever more combative and paranoid, becoming fearful of being killed in retribution by “Booth’s avengers.” He eventually secured a post as an assistant doorkeeper for the Kansas state legislature, but after threatening members at gunpoint, a judge declared him insane, and he was confined to an asylum, from which he escaped in short order, vanishing from history.

1. Booth’s last words

Shot through the neck and paralyzed by the bullet fired by Sergeant Boston Corbett, John Wilkes Booth suffered a lingering, painful death over the next several hours at Richard Garrett’s Virginia farm, on the early morning of April 26, 1865. The soldiers who captured him moved him to the front porch of the Garrett house. Unable to find relief from excruciating pain, despite the best attempts of his captors to make him comfortable, he begged investigator Lafayette Baker to “kill me, kill me.” Baker refused: “We don’t want to kill you. We want you to get well.” Barely able to whisper, he asked detective Everton Conger to “tell my mother I die for my country.” Near the end, he requested one of his captors to raise his hands, and looking at them, he muttered, “Useless, useless.” Booth then died, as the sun dawned, just two weeks shy of his twenty-seventh birthday.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a 4″x3″ slide depicting John Wilkes Booth leaning forward to shoot President Abraham Lincoln as he watches Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. 14 April 1865. It is in the public domain and appears here courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The image of John Wilkes Booth, Edwin Booth and Junius Booth, Jr. (from left to right) in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in 1864 is in the public domain and also appears here courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Do you think the Lincoln conspiracy was in response to the Dahlgren Raid?

Possibly, Bob, and that is more likely the case if Booth were indeed a Confederate agent, or if he were hired by Confederate agents. You may recall that I addressed the Dahlgren raid here: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2015/04/american-brutus-what-motivated-john-wilkes-booth.html

Excellent article, marred only by its embrace of the standard view that the Booth conspirators ever really wanted to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson (along with Lincoln and Seward – both of whom they certainly did want to kill). Lincoln’s nomination of the Southerner Johnson as VP in 1864 was a monumental mistake, in that it made possible a clear and direct path for restoring a Southerner to the Presidency: assassinate President Lincoln! The standard account of George Atzerodt getting drunk that day, and forgetting to carry out his part of the plan by killing Johnson, etc., is absurd on it face. If you were a Lincoln-hating member of the Confederacy, why would you want to kill Lincoln AND Johnson both? Leaving Johnson alive WAS the plan!

Thank you for this comment. Though Atzerodt’s assigned role in the conspiracy, like many aspects of Booth’s assassination plot, cannot be known with certainty, the military tribunal believed that Atzerodt was designated to kill Johnson. Atzerodt was staying in a hotel room at the Kirkwood House right above Johnson’s room, which lends much credence to the idea. Atzerodt himself claimed that David Herold, and not he, had been chosen by Booth to kill the Vice President. So it seems likely that one of the two had been tasked with this murderous job.

Your assumption that because Johnson was a Southerner, Booth et al. wanted him to be president is faulty. Johnson was widely seen as a traitor by Southerners and had done nothing to give any hope to Booth and like-minded Confederates that he was a friend of the South. Indeed, he had favored a harsh policy toward pro-Confederate sympathizers as military governor of Tennessee and as Lincoln’s vice-president-elect. Recall also that Booth left a note for Johnson at the Kirkwood house once he realized that Atzerodt had left the hotel without killing the vice president (“Don’t wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J Wilkes Booth.”) Though Booth’s intent is not entirely clear, this was likely an attempt to implicate Johnson in the assassination plot, thereby sowing further confusion in the North, and making trouble for the hated Johnson.

Thanks for the reminder- I”m getting older. Two outstanding pieces. Please keep them coming, very enjoyable.

interesting that the presidential assassination that we know the most about, was a well-thought out plan (ie, a conspiracy). but the one we know the least about is attributed to the “lone nut”.

hmmmm

Mary Lincoln may have been Booth’s unintentional accomplice. Her shabby treatment of Julia Grant led the latter to make an excuse for her and her husband to be out of town on the fatal night. Had Grant been on hand, who knows how things would have turned out? It is possible that Booth would have been minus some teeth–or that Mrs. Lincoln would have had even more blood on her hands.

I retract the last clause of my comment, because it doesn’t make sense.