I have had a lot of response to my column on Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s book Democracy — The God That Failed, most of them enthusiastic. A surprising number of citizens of this democracy have lost faith in the state, democratic or otherwise.

It is amazing how seldom we ask the most basic questions: What is a state, anyway? Where does it get its authority? Might we be better off without it?

These are serious questions. One scholar estimates that during the twentieth century, states murdered about 177 million of their own subjects—and that does not count foreigners killed in wars. In order to justify their own existence, states had better be doing someone a lot of good, or be able to show that in the absence of states, even more people would have been slaughtered. Neither proposition is credible.

“Wait a minute,” someone will say, “you’re mixing apples and oranges. Sure, there are bad states, like the Soviet Union, which murder millions, but there are also good states, which don’t murder people and which protect their people from bad states.”

Well, it is possible that a mildly rapacious state may afford us some protection against a much worse one, just as one neighborhood gang may offer safety against another. But all states are rapacious, almost by definition.

What is a state? It is the ruling body in a territory, which claims a monopoly of the legal right to command obedience. It may demand anything—our earnings, our services, our lives. Once the right to command is conceded, there are no limits on its power.

Many people think a state is a natural necessity of social life. They can hardly conceive of society without the state.

This would be plausible if the state confined itself to enforcing natural moral obligations—that is, if it protected us from robbery, murder, and the like, otherwise leaving us alone. But what if the state itself robs and murders, claiming the authority to do so?

Any two men will usually agree that neither may justly take the other’s property or life. Nor does either owe the other obedience; that would be slavery. But somehow the state claims what no individual may claim—a right to the lives, property, and obedience of all within its power. The state asserts its “right” to do things that would be wrongs and crimes between private men. And most people accept this claim! They think they have a moral duty to obey power!

So why do people think they have this duty? Of course, as the philosopher Thomas Hobbes argued, the state ultimately rests on its power to kill (or otherwise harm) those who disobey it. But this is a threat, not a duty. If I demand your money at gunpoint, you will obey, but the gun does not create an obligation, merely a menace.

But the state pretends that all its demands, however arbitrary, are moral obligations, even though those demands rest on force. If it were confined to demanding only what decent people do anyway—refraining from murder, robbery, et cetera—it might be bearable. But it never stops with reasonable moral demands; at a minimum, even the most “humane” and “democratic” states use the taxing power to extort staggering amounts of money from their subjects. The predatory tendency of the state is inherent and expansive, and nobody has found a way to control it. No control can long withstand the monopolistic “right” to demand obedience in every area of human activity the state may choose to invade. Systematized force—which is all the state really is—follows its own logic.

Legal forms, moral rhetoric, and propaganda may disguise force as something it is not. The idea of “democracy” has persuaded countless gullible people that they are somehow “consenting” when they are being coerced. The real triumph of the state occurs when its subjects refer to it as “we,” like football fans talking about the home team. That is the delusion of “self-government.” One might as well speak of “self-coercion” or “self-slavery.”

No, the state, now grown to a monstrous magnitude, remains what Albert Jay Nock called it: “our enemy, the State.” Maybe Professor Hoppe is dreaming. Maybe anarchism could not be sustained. Maybe the evil of systematized force can never be eliminated in this fallen world. But why pretend such an evil is a positive good?

Copyright (c) Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation, www.fgfBooks.com. Reprinted with permission.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

There are some problems here. First, the state, which can serve as a synonym for big government, is an amorphous monolith in that its shape can’t really be defined but it is always the same. In reality, the state can have several shapes and they are not all the same.

The conservative approach briefly described here says that the state should take a minimalist approach to governing in that it should only be concerned with natural law. But in saying that, there are two problems. The first problem is that not everyone is agreed on what natural law is. The same-sex marriage controversy has shown this to be especially true. Second, not everyone agrees as to how natural law should be implemented in a society that is growing in its complexity and interdependencies.

There is another problem of course. The shape of any state that is based on natural law is similar enough to the shape of any state that is strongly based on any ideology so that it must be based on elite-centered rule. And as when the state is based on any ideology, you must have the right elites in charge who will interpret and apply the ruling ideology or natural law. And for those elites to keep their position of authority, especially when there is controversy and dissent, they must use power over the rest of the people with the amount of power being more/less directly related to the degree of dissent and resistance present. The reason why our Constitution was written was so that the state would have more power to deal with dissent and uprisings like what occurred with Shays Rebellion.

So it seems that the problems mentioned in the post above regarding the state’s abuse of power are not alleviated by restricting the it to enforcing natural law only.

Sobran had it right. He fell away from the mainstream Right and was regarded as too radical. Sadly I suspect that many on the Right still don’t realize the threat that they and the nation face as power, deficits, and and federal controls wend their way into the intrinsically corrupt mega-State.

This article, and my general browsing of your content afterward when I visited your homepage, have just added you to my bookmarks toolbar! I have never heard of this site before btw.

What does these revolutionary ideas in this conservative site?

“Who are these insolent men calling themselves the French nation, that would monopolize this fair domain of nature? Is it because they speak a certain jargon? Is it their mode of chattering, to me unintelligible, that forms their title to my land? Who are they who claim by prescription and descent from certain gangs of banditti called Franks, and Burgundians, and Visigoths, of whom I may have never heard, and ninety-nine out of an hundred of themselves certainly never have heard; whilst at the very time they tell me, that prescription and long possession form no title to property? Who are they that presume to assert that the land which I purchased of the individual, a natural person, and not a fiction of state, belongs to them, who in the very capacity in which they make their claim can exist only as an imaginary being, and in virtue of the very prescription which they reject and disown? This mode of arguing might be pushed into all the detail, so as to leave no sort of doubt, that on their principles, and on the sort of footing on which they have thought proper to place themselves, the crowd of men on the other side of the channel, who have the impudence to call themselves a people, can never be the lawful exclusive possessors of the soil. By what they call reasoning without prejudice, they leave not one stone upon another in the fabric of human society. They subvert all the authority which they hold, as well as all that which they have destroyed. (…)

The state of civil society.. is a state of nature; and much more truly so than a savage and incoherent mode of life. For man is by nature reasonable; and he is never perfectly in his natural state, but when he is placed where reason may be best cultivated, and most predominates.”

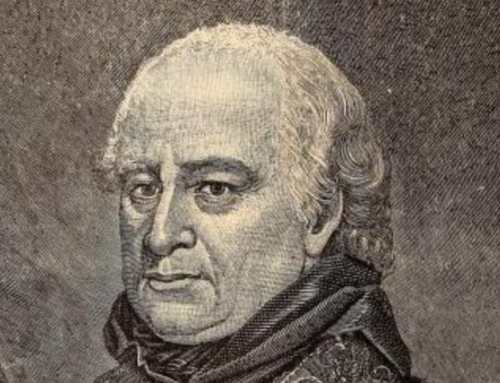

Edmund Burke, An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs