“If there’s one thing I learned from seminar, it’s that saying what something is NOT, is not the same as saying positively what it IS.”

“If there’s one thing I learned from seminar, it’s that saying what something is NOT, is not the same as saying positively what it IS.”

Part I: Before

If you choose to go to St. John’s College in Annapolis, you will begin your first day of math class by setting forth with definitions, axioms and postulates.

So let me define myself for you—as I was before St. John’s—in a single word. Farouche. You will uncover the shades of meaning in the French word during your junior language class: “sullen or shy in company” or “fierce” or “wild,” by turns.

Before I came to St. John’s, all I knew about my future was that I wanted to be a cross between Dorothy Parker and Emily Dickinson.

For the axiom, I’ll borrow one from the old Frenchman who loved his Latin, Rene Descartes. I think therefore I am…I love, therefore I live.

Postulate: Success is nothing other than facing the risk of failure without flinching.

***

You will begin your first ever seminar at St. John’s with an opening question. This will be asked by the tutor. The tutor is likely older and perhaps much wiser than you. (They may have read the work for the first time too, but they are paid to think harder while you pay to learn how—not “what”—to think.)

Opening question: “If the first two years were Hell, and the last two years were Heaven…Is the sum total of those years Purgatory?”

Perhaps the best one can say about a college experience is “No Regrets!”

***

Some come here for wisdom, others for truth. I chose St. John’s for three reasons:

- I hated citing secondary sources to get good grades on papers. I believed that citing the actual text proved my points better.

- I already knew how to swing dance.

- This school seemed like the least of all evils

Consider this tale of application woe…

The Ivies had turned me down…and my “safety school” and an all-girls school had given me the biggest scholarships.

The all-girls school no longer exists. I remember when I visited its campus my enunciation was so poor that the admissions counselor took me to the stables when I’d said I wanted to check out the “writing” program. Second, I went to the head of the visual arts department. He asked me a few questions. He concluded, folding his hands calmly at his desk and looking me in the eye: “We would love to claim credit for you, but you won’t learn much from us. Have you considered Yale?”

I took this as a sign that I would not fit in and turned down a 75% scholarship. My “safety school” soon hosted its orientation day. It was summer 2000. I was signing up for classes. I had tested out of a foreign language requirement, but I went up to the head of the French department. Speaking to her in my solid, schoolgirl French, I asked to take a class in her department. She was delighted. With a “Cherie” and a nod, she placed me in her Senior level class: La Chanson de Roland. (I already had the Existentialists, Molière, and Baudelaire covered). Next I signed up for astronomy, some nonsense survey seminar about feminist heroines in film culture from 1920-1980… and then sat down in front of the man whom I assumed would be my department head in Creative Writing. I only wanted to major in Creative Writing because I was already writing and I knew that this man took one senior every year and got them published. (Not e-published. Not print-on-demand. We’re talking hardcover book contract bookshelf-in-store published.)

He sized me up as I asked him if I could take one of his fiction workshops as a freshman. (This was not done in the first year. One didn’t declare a major until the following year.)

He clasped his hands around his knee and sat back. “You’re the first person with a spark of intelligence in her eye that I’ve seen all day.”

I will never know whether he meant to flatter me, whether he said that to most students who had the gall to do anything out of the proper order, or whether he was secretly telling me to go elsewhere.

If Leibniz is right and this is truly the best of all possible worlds, I will assume his motivation was the latter. After climbing into the car to leave, I burst into tears in front of my father. “I can’t go here.” I explained how the school treated me as if I was smarter than I ought to feel… that I was afraid I wouldn’t learn anything, if what that man said was right. One would never have such a problem at St. John’s, you see.

All I knew about St. John’s at that time was what I’d read in a slim, two-color basic brochure. It was pretty much a reading list and nothing more. A colleague of my father’s had passed it on to me. She had followed her husband to St. John’s sometime circa 1970. He was a math whiz who had turned down Harvard to go to SJC. She came to think of it as the greatest period in her life (and drank only the best scotch during it).

I had tossed the brochure aside having no use, said I to my father, for Ancient Greek. At that time, in my junior year of high school, I was planning on being a visual artist: a photographer and fashion designer, who wrote fiction in her spare time.

The summer before my senior year of high school I saw Saint John’s campus for the first time, quite by accident, on a little historical tour of Maryland’s capital. I saw the brick everywhere, and the quiet, conservative dress of the few students strolling to and from class (Febbies, I would later learn). I said to my mom, “I never want to go to a place like this!” We passed by the bookstore without even going in.

But, after these disappointments, I learned where I did not want to go. So I’d expend no more energy finding a place where I did. I’d just take a risk. After all, my dad was the one who was paying for it, and he loved the place! So I negotiated a shrewd bargain.

I withdrew from my “safety school” and applied to St. John’s, on the condition that my dad support me for a year-off during which I would write my first novel, Random Acts of Beauty and Violence. He agreed, provided that I lay a certain number of pages at the breakfast table at the end of each week. We shook hands. Done deal.

Part II: During

Lest you think that I resisted St. John’s because I did not like to read, rest assured I was enamored of the written word from a very young age. I’d read encyclopedias on rainy weekends. I’d declaimed Shakespeare happily and always read the unabridged editions of anything we read in anthologies.

In fact, the first thing my parents admired about their child was her ability to read. I was three, perhaps, when I began spouting off the words on the page. Only after one of the pages stuck together one night did my dad realize I had simply memorized the sounds he’d made in relation to the pictures.

Pictures have just as much pride of place for me. I had been trained for four years in a public magnet arts high school to be a visual artist. My painting teacher, my drawing master, and my department head were all shocked when I revealed I was going to St. John’s.

Did I regret it? No. Did I hate it sometimes? Yes.

Unlike many compatriots at the College, I did not find any earthly value in wondering about “a thing in itself” or Truth with a capital-T. I preferred Aristotle’s pragmatisms to Plato’s Socrates.

What one moment do I recall from Freshman Seminar? Maybe it’s not even wisdom… but Mr. Tomarchio said to us (someone was complaining about the exaggerations of Greek Tragedy): “I think,” he mused aloud, “that Greek Tragedy is like opera. You will understand it better when you are older.”

This is true. I say this because I had no big love of opera until falling for Tristan und Isolde at St. John’s. Even then, it took time for the seeds planted by freshman chorus and sophomore seminar to grow.

Five years after graduating, I became a Fellow in the National Endowment for the Arts Classical Music and Opera Criticism program. We binged on ten days of classical music in NYC. Nine overnight music reviews. Back stage tours of Carnegie Hall, the pit of the Metropolitan Opera…and one amazing night, we heard Gergiev conducting René Pape in Boris Gudanov. Now I regularly host mezzo sopranos and baritones to champagne soirees in my downtown apartment. It’s not the glamour, but the depth of what they do that strikes my core. St. John’s neglects Ben Britten’s Rape of Lucretia. After hearing my friends mount a live production, I couldn’t forget it. Opera, like the Greek plays, keeps one alive to what is δεινός—uniquely human and “terrible or wond’rous”—about life.

Greek Tragedy, you will realize with age and experience, is no exaggeration. It merely condenses into a month what happens in years… into a day, what happens in months… into an hour what happens in days. It’s one of the few emotionally ripe things you will read at St. John’s, except maybe Austen and Eliot (or Les Fleurs du Mal—the emotionally overripe).

When life piles upon you… a suicide of a cousin, a stay inside a place Zelda Fitzgerald knew well…you remember Antigone. You remember the raw, feminine anger of Clytemnestra. I played Clytemnestra once, with the magic circling Greek Chorus around me. At no other school would such a thing happen: students in spare time learning with tutor and choreographer how to voice Tragedy, to invite its spirit—timeless, ever-vengeful, ever-living—into the Great Hall of McDowell for our entire community and visiting parents.

When in time of adversity, when alone on a dark Baltimore street, when in hospital, I sing to myself, sometimes loud, sometimes soft: αἴλινον αἴλινον εἰπέ, τὸ δ᾽ εὖ νικάτω—“Cry sorrow, sorrow, but let the good prevail.”

Speaking of sorrow, the good, and weeping, I should probably tell you about finding love at St. John’s College. For at no other school could one, I think, have occasion for cathexis to meet the chthonian, both in class and outside. My enriched life sprung most unexpectedly from the ashes…

Some grads married their college sweethearts (the couple the first to divorce from my years, split, in part, over Hegel). Meanwhile, my path lay between being a defender of Artemis, militantly feminine, and a Christian nun. In junior year, it took the slightest diversion…

Only at St. John’s will you have a student linger at the breakfast table with another, hormones surging, to find them addressing each other “Mr. and Ms.” And when they, determined to skip junior lab, decide instead to go to his room and smoke a clandestine cigarette, he will take Plato down from the shelf and read aloud.

As Simone Weil aptly puts it: “Love is not a consolation, it is a light.”

So this young, audacious whelp of a man read to me from Plato’s Phaedrus: “This discourse that goes together with knowledge and is written in the soul of the learner: that can defend itself, and know to whom it should speak and to whom it should say nothing. Living speech.”

(It may happen that some scapegrace intellect will invite you up to his or her room with the boast: “check out my translations.” They will also offer you other forbidden fruit. Buckle your seatbelt for a bumpy or boring night, accordingly).

And this blunt soul passed off the book to me. Trembling I read, of the chariot and the two horses, one dark, one light: “Now when the driver beholds the person of the beloved, and causes a sensation of warmth to suffuse the whole soul…and the obedient steed, constrained now as always by modesty, refrains from leaping upon the beloved; but his fellow, heading no more the driver’s goad or whip, leaps and dashes on, sorely trembling…for a while they struggle, indignant…so it happens time and again, until the evil steed casts off his wantonness…the soul of the lover follows after the beloved with reverence and awe.”

So imagine me in my shivering innocence … how we look into each other’s eyes … he grins. We hear the bell for class. We continue to stare. He asks me if I understand.

I nod. But then suddenly he grabs my hand, and we dash to Mellon to go to our respective next-door lab classes, laughing at our shared secret. Mr. Burke looked at me, astonished, I think, at my flush and excitement. I spoke more than usual that day, though I fear I prepared less.

The lover, you see, is indeed the mirror in which you behold yourself.

And I beheld myself differently after that… His gift to me on my twenty-first birthday was a black volume of blank pages. He’d wedged it in my doorway.

My thank you note was Surrealist. I went up to a book of French poetry and turned to a random page, which I copied out: “La poèsie se fait dans un lit comme l’amour / Ses draps défaits sont l’aurore des choses.” André Breton. “Poetry is made in the bed, like love / Its unmade sheets are the dawn of things.”

Yet poetry fails in a place where you begin with Hobbes… We saw each other only rarely after that. Mostly on a dance floor. Never touching.

But I began to be myself, more than ever, reveling in what made me, me. I become better able to communicate it, to take pride in it—my strength and weakness, the passion and the intellect, the feminine and the masculine. I began to follow the immortal command of Will Blake: “Lift up thy head.”

Because our “white horses” led, we are now brother and sister in arms and heart. A decade since we first spoke, we still know each other. The adventures we’ve both had, so unpredicted, manage to cross our paths now and again, and give us renewed strength.

I think perhaps we are following the same god as one follows a star. Without St. John’s would I have ever beheld it? Would my heart have knitted things to intellect and made my life truly begin?

I believe that young man, unwitting divine messenger, like a Mercury or Pan, was the window—the mirror (skipping the unmade sheets)—through which I began to behold something like the dawn of things.

And to think, I’d almost left the school the year before…I only stayed based on the conviction of just one of my tutors that I’d enjoy the subjects of junior year in unexpected ways.

He was right.

It was the year that I learned that reverie and intellect can walk hand in hand. One can be dutiful and be independent. Most schools have no way, with their hordes and their majors and hapless electives, to teach one that.

Part III: After

You will realize that you loved your time at Saint John’s in the oddest ways. In 2007, I’d found myself stranded on a tiny, secluded island in the height of azalea season with a young man who’d thrown a party for his twenty-five bestest friends—many of whom were wealthy, unattached trust fund types. I knew finally that I was indeed that strangest of all creatures—a “Johnnie”—when I demurred drink, donned a kimono, and snuck away from the shenanigans to be solitary.

Solace was a stack of books I’d found in a dusty cupboard. With strange delight, I found myself staying up to read a novel (a novel?!) by St. John’s Program cofounder Stringfellow Barr called Purely Academic. I tried to explain why this seemed extraordinary to two drunks who stumbled my way. They did not understand.

Who does understand? Well, for starters, the two men who hired me at my first job in finance. And the first six-figure-making copywriter who trained me… And now I’m set to become the first female publisher in my male-dominated division of the biz. They know that there is no difference between the seminar table and the marketplace. Literally, they’re called Agora Publishing.

No door is closed to me. I walked my way into the hearts and minds alike of the Lyric Opera Baltimore’s board, without having hundreds of thousands of dollars in my back pocket. Meanwhile, down in D.C., I’m on the board of directors of PostClassical Ensemble. Around the meeting table are major philanthropists, partners, consultants and I hold my own with my endurance and adaptability. Also, the trick learned at the college of knocking back fine scotch or whiskey with aplomb (and still debating your enemy) is not to be underestimated in the “grown-up” world of work.

I know freedom to be prized above all things, such as only belongs properly to those that “shift for oneself.” I love my work, and working hard now feels easier than it ever has—easier than staying up all night in high school working on a drawing for tomorrow’s class… Or spending my entire Christmas break translating Greek for Mr. Grenke — who never even collected the assignment. (He’d laughed. He’d said those who had actually done it all would be rewarded by the doing it. I hated him for that. But he was right.)

There is, of course, a time and place for dreaming; it might well be called St. John’s College. Yet today, I am debt-free, with a year’s salary in the bank, just in case. I do my best to mentor those coming up behind me in the hopes they too shall find a place that suits and satisfies as much as mine has.

St. John’s, you see, is the best place to go, if, in fact, you don’t know where to go. But, be warned, you must already have in you the ambition to go somewhere. Somewhere big and unexpected.

You must take every bit of every reading under your belt and gird your loins with it. Or you will not be able to properly stare failure in the face… and succeed.

***

The thing that sticks with you most after you’ve left the college is the correspondence you will have. Because everyone tackles the same material — the so-called Great Books — our shorthand vocabularies enrich our lives forever. Our experience unites us beyond the confines of what some besmirch as “an ivory tower.”

I still pen letters to my sophomore year roommate. She left the college in junior year to marry a Johnnie and live on a farm by his side, an equal partner in their home business while raising three beautiful sons. I ended my most recent letter to her with this determination: “My goal is to run away from nothing, but to learn what is worth pursuing.”

She wrote back within a week: “My dear, you’ll be a St. John’s tutor one of these days!”

I laughed out loud as I read this line. I dashed off a quick note back: Je pense que je suis “une femme qui est trop gaie” pour çela, as Baudelaire might have put it. To be sure yours truly has only had flings with philosophy, and to put it that way means I am no philosophe! One must be dominated, absorbed, pecked night and day by the love of Truth. No. Too much Life to be lived!

And there are still a very many pages to fill in my friend’s black book.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

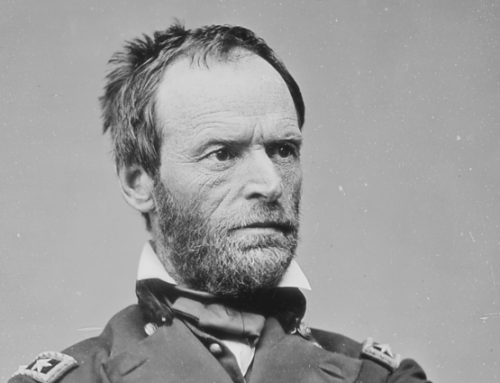

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.

Leave A Comment