Few Americans spend much time thinking about the vagaries of administrative law—the rules and procedures our government uses in formulating and enforcing regulations—let alone its effects on our lives and liberties. Anyone warning of the imminent demise of Americans’ liberties is likely to be dismissed as a kook. Anyone claiming to find such dangers in the actions of fussy little bureaucrats toiling in the bowels of federal agencies most likely would be simply laughed at.

Few Americans spend much time thinking about the vagaries of administrative law—the rules and procedures our government uses in formulating and enforcing regulations—let alone its effects on our lives and liberties. Anyone warning of the imminent demise of Americans’ liberties is likely to be dismissed as a kook. Anyone claiming to find such dangers in the actions of fussy little bureaucrats toiling in the bowels of federal agencies most likely would be simply laughed at.

Philip Hamburger, a distinguished legal historian teaching at Columbia Law School, has no alarmist, overwrought story to tell. Nonetheless, his latest book is intended to spark reconsideration among lawyers, political scientists, and educated citizens about the effects of administrative law on American government and on Americans’ rights and liberties. His central point: Administrative law is—not tends toward, not encourages, but in itself is—a form of arbitrary power inconsistent with our traditions of ordered liberty.

In this powerful book, Hamburger argues that constitutional government grew from people’s attempts to rein in arbitrary power. In particular, kings long had claimed the absolute power or prerogative to rule outside and above the law. They claimed the right to act in an arbitrary manner, answering to no one for their actions. Over time, this prerogative power was limited by legal procedures, though it continued to show itself in claims to act above the law in times of “necessity,” particularly in time of war. The American constitutional achievement was to enshrine both procedural due process (most importantly jury trials and rules against self-incrimination) and the separation of powers as checks on arbitrary power. The great constitutional thinker Montesquieu had defined the combination of legislative, executive, and judicial power as “arbitrary” because it was above law, meaning that the one wielding it had to answer to no one. And, as Americans had long known, one who need not answer for his use of power inevitably will use it for his own ends and come to tyrannize the people. Customary, common law had enshrined due process as the most effective protection for people facing the overwhelming power of the state, and these protections, first set down in Magna Carta in 1215, developed into powerful tools against arbitrary proceedings aimed at eliminating opposition to arbitrary governmental actions.

A key reason why Americans rarely concern themselves with administrative law is that few of us have any interaction with it, or with those who apply and enforce it. Or so we think. Administrative law has had a major role in reshaping our economy and, increasingly, our individual, even private lives. Where previously only large corporations had to fear administrative rules and procedures, any one of us now could be in the crosshairs. In point of fact, this has been the case for many decades, as anyone unfortunate enough to suffer an audit from the IRS knows full well. But few of us (fingers crossed!) receive the “full audit,” hence we all see it as an extraordinary catastrophe we fear, but hope never to experience. These days, however, even the solitary farmer who wants to drain a pond on his property has reason to fear a visit from government functionaries, in this case from the Environmental Protection Agency. And pity the farmer who gets on the wrong side of the protectors of the environment.

Defenders of administrative law argue that it is necessary for the government to meet the challenges of an advanced industrial society. We will not have safe food or drinking water, will not be able to insure ourselves against discrimination or bad economic times, the argument goes, unless we recognize agencies’ need and right to write their own rules (Congress does not write most of the rules we must follow, federal agencies do) and enforce them in a “streamlined” fashion.

It is precisely this “streamlining,” justified on the old, absolutist grounds of “necessity,” that undermines protections for citizens and limitations on the power of government functionaries to bully us into falling into line with their will-of-the-moment. Hamburger focuses on the means used by agencies in enforcing their rules—means that provide precious little protection for the protections Americans once recognized as our birthright.

First applied only to powerful corporations, many of which cooperated in setting up agencies to keep out unwanted competition, administrative rules openly violate constitutional limitations and procedures. Like the old High Commission of Henry VIII, today’s bureaucratic powers can force organizations and individuals to testify against themselves, including by forcing them to provide answers to administrative questions, backed up by the power of the subpoena. All too often, these questionnaires are, in reality, attempts to find dirt on regulated people and entities in an attempt to gain leverage over them. With no one actually accusing them of any wrongdoing, those caught in the government’s crosshairs must answer questions without knowing that they are charged with anything, without the protections of a grand jury, and without even a neutral judge. Instead, they must defend themselves in inquisitorial proceedings overseen by administrative law judges trained to oversee a process that favors the government.

Most of those caught in the administrative machinery never enjoy even the limited, sub-constitutional protections of administrative law. Administrators feel free to bully those they regulate into signing “consent decrees” agreeing to ad-hoc, one-sided rules and policy goals with no basis even in regulatory law, in order to avoid being sucked into costly administrative litigation. And, even below this level of coercion, administrators themselves habitually change enforcement manuals and issue various decrees under ironic labels akin to “letters of advice” changing and imposing new rules, safe in the knowledge that those they regulate lack the will and wherewithal to put up much of a fight.

These methods likely will not go away soon. Indeed, they are likely to expand, despite their clear violation of basic customs and understandings of our constitutional order. In part this is because few of us, and almost no one among our political elites, has any sympathy for the corporate entities and officers who generally are its victims—and who often deserve some blame for cooperating in creating and maintaining a system that by its nature stifles economic competition. But more and more of us, we mere American citizens, are affected by these methods and procedures. These arbitrary methods are used to alter economic policy and to shape markets and market choices. “Green energy” is only the latest bureaucratic fad, being added to almost maniacal “safety” concerns that list sand as a hazardous substance even while failing to protect us from obvious dangers (remember that poisoned dog food and those lead-painted toys from China?). Small businesses fail or never get started because entrepreneurs can afford neither the time nor the expense of defending themselves against arbitrary enforcement of arbitrary rules carried out in arbitrary proceedings. And so our economic system becomes increasingly centralized in the hands of those few with the wherewithal to combat or co-opt administrative structures and procedures. This is the reality of crony-capitalism, the product of arbitrary power exercised in the name of the people but for the advantage of ideologues in government and the most powerful and well-connected officers of corporations.

Nowhere does Hamburger claim that the sky is falling, or that we have succumbed to a leviathan state. What he does very well is demonstrate the nature of the power we have allowed an increasingly large role in the running of our government. It is up to us to demand that those who claim to be saving us from all kinds of danger through government action do not allow their drive to “do good” to so expand the realm of arbitrary, administrative power that our government and society no longer will deserve to be called “free.”

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

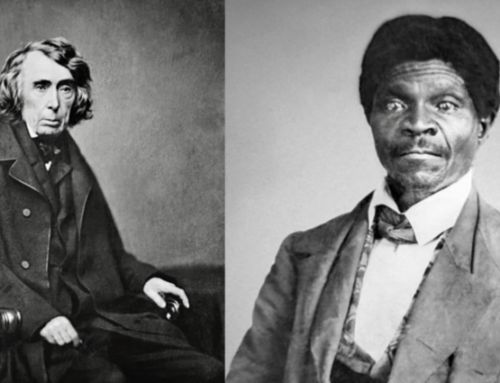

Editor’s note: the featured image was provided by the U.S. Government, and is in the public domain.

What has happened to us? How has this happened? How has one of the most revolutionary governments ever created on this planet, one that actively built in measures to restrain itself from abuses of powers, traded its marvelous theocracy for a petty, boring monarchy. How have we, like the ancient Israelites, become so tired of what made us special and desired to be like anything else?

This is the text of the proposed amendment that Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and his people put forward in the Senate within the past week. Cynical musings about which side was more cynical, the side that put forth a bill designed to fail or the side that allowed the bill to live long enough to pontificate on how it would fail miserably, aside, the amendment sends shivers of terror down my spine.

“Article- Section 1. To advance democratic self-government and political equality, and to protect the integrity of government and the electoral process, Congress and the States may regulate and set reasonable limits on the raising and spending of money by candidates and others to influence elections.

Section 2. Congress and the States shall have power to implement and enforce this article by appropriate legislation, and may distinguish between natural persons and corporations or other artificial entities created by law, including by prohibiting such entities from spending money to influence elections.

Section 3. Nothing in this article shall be construed to grant Congress or the States the power to abridge the freedom of the press.”

Now I am not a “the skies are falling” type of man. I try to be level-headed. But this amendment seems to me to be the tipping point, or the sign that we have just gone over the tipping point. When the party of Government openly puts forward the suggestion, even a suggestion designed to fail miserably, that the First Amendment of our Constitution is somehow inadequate to meet the needs of the political class in Washington, we are in trouble.

This process did not happen overnight. It has been happening for over a hundred years, and the slow conditioning of the American people is nearing completion. Exactly how long the cushioned political class will get to enjoy the rewards of their many years of long labor I do not know. I feel almost a perverse desire to start a betting pool on which trillion dollars of debt will be the one to break out backs…

Regardless, the lessons of the XXth Century are clear. The best way to achieve systematic and unquestioned control of a populace is not through violent revolution and rapid conquest, but through the slow and patient hands of Fabians.

The Democrats/Progressives have been trying to run this piece of legislation through Congress for a number of years now, in various incarnations. They will continue to do so until they are successful.

Yet, bad, tyrannical law is also promoted by Republicans and “Independents” Look at NDAA: it was offered numerous times – repeatedly, via the collaboration of McCain and Lieberman – before it was passed and written into law.

Since neither party is likely to do anything to rein in legislation by regulation, we will continue to suffer these insults and damages until someone actually causes the heads of these agencies – and their local minions who actually are their “boots on the ground” – to experience significant and personal consequences for their actions. I see no other recourse, since neither the courts nor the election process yield results. When the soap box, the ballot box, and the jury box fail us, what is left?

I presume that this article and Hamburger’s book deal primarily with federal administrative law. At the state level, though, things are quite different.

At least 42 of the 50 states (last I checked) have some kind of body — most commonly, a committee of legislators — that reviews executive branch agency regulations before they take effect, to insure that, at a minimum, they do not go beyond the authority granted to the agency by statute. (I work for one of these state oversight committees/agencies.) In some states (including mine) the committee has authority to prevent rules from taking effect, and to require changes, if they are found to be contrary to the public interest or not grounded in statutory authority. In other states this body is merely advisory.

No comparable body exists at the federal level, in part because the U.S. Supreme Court (INS vs. Chadha, 1983) declared this type of intervention to be contrary to the separation of powers. States, however, get to decide that question individually based on their own state constitutions. Some state oversight bodies have been sued on that basis (violation of separation of powers) and had their authority severely limited or abolished; others have been affirmed.

Personally, I think this kind of legislative oversight does a good deal to insure that rulemaking doesn’t become a law unto itself against which the ordinary citizen has little to no recourse. An agency like the one I work for at least gives the citizens a fighting chance.