Welcome to the Class of 2013 [this is a Convocation Address delivered in 2009 at St. John’s College, Ed.] and to your families. To the rest of our college community, welcome back. Welcome, friends all! I came to a rather startling realization over the summer as I was preparing to greet our newcomers: that I had returned to this college to take the position I now hold in the year in which most of our incoming freshmen were born. The years have passed quickly, it seems to me now, and my appreciation for the community of learning I joined back then has grown, as my friendships within the community have deepened. I think I became a wee bit sentimental as I ruminated upon my first year as a student at St. John’s more than 40 years ago. My Greek has gone rusty, but as with most all of memory, the things learned first are remembered best, and I have kept with me over the years two Greek sentences I recall reading in my first days at the college. Xαλεπά τα kαλά and Κοίνά τά τών φίλων.

Welcome to the Class of 2013 [this is a Convocation Address delivered in 2009 at St. John’s College, Ed.] and to your families. To the rest of our college community, welcome back. Welcome, friends all! I came to a rather startling realization over the summer as I was preparing to greet our newcomers: that I had returned to this college to take the position I now hold in the year in which most of our incoming freshmen were born. The years have passed quickly, it seems to me now, and my appreciation for the community of learning I joined back then has grown, as my friendships within the community have deepened. I think I became a wee bit sentimental as I ruminated upon my first year as a student at St. John’s more than 40 years ago. My Greek has gone rusty, but as with most all of memory, the things learned first are remembered best, and I have kept with me over the years two Greek sentences I recall reading in my first days at the college. Xαλεπά τα kαλά and Κοίνά τά τών φίλων.

The first can be roughly translated as “Beautiful things are difficult” or “Noble things are difficult.” The second can be translated as “The things of friends are common” or “What friends have, they have in common.” Back in the days of my youth we used a different Greek grammar book, so this last week I took a peek at the Mollin and Williamson Introduction to Ancient Greek that you will be working with in your first semester of the Greek Tutorial. And there they were, the same two sentences, buried in an early lesson on the attributive and predicate position of the definite article, and I rediscovered something I once must have known about the two sentences I had carried with me all these years: that they are both nominal sentences with the article τά in the predicate position, making it possible to write intelligible, whole sentences without the use of a verb. (Grammar is a handy tool, don’t you think?) Well, I was pretty sure that I had not committed these sentences to memory for the substantive-making power of the article τά. It’s more likely that I remembered them because they were both quite short, and perhaps because they appeared to carry a mystery and a whiff of truth in them that I might untangle for myself if only I worked on them long enough. I felt justified in this interpretation when I read in this new text that “nominal sentences are best suited to the impersonal and timeless character of maxims or folk-sayings.” (Mollin and Williamson at 31)

I wanted to understand better the little maxim Κοίνά τά τών φίλων “The things of friends are common.” The sentence seemed to capture a beautiful thought, and I had the efficient notion that if I made the effort to understand this maxim better, I also might come to see why “beautiful things are difficult.” Two birds, one arrow — so to speak!

So, I begin my reflection by asking whether this little maxim means that friends share what they have, or that they ought to share what they have. Today, I give you half of the lunch I packed for us both, and tomorrow you will share yours with me. But the sandwiches we eat are hardly common to us both; quite the opposite, they are rationed out separately to each of us, albeit equally. We may each have an equal share in a good thing, but not a common good. We each consume what the other does not and cannot consume. So it is with all sorts of goods, earthly goods, goods that are external to us; what I give to you in the spirit of sharing with a friend is something I will no longer have after giving it. I will have less of it after sharing it than I did before I shared it, however good and generous my act of friendship has been, and however much I imagine I may have gained in the improvement of my character by sharing it.

But what then are the things that could be common to friends? What kinds of things can truly be held in common without having to be shared or meted out among friends? I suppose things of the soul are of this nature, things that belong to the heart, the spirit, or the mind, things that belong to our inner lives. We both may love a single object or a person without our having to share that love as we might share the expense of a gift to the beloved one. My love doesn’t grow less because you love too. And of course, if we should actually love one another, that love is surely greater and stronger for it being reciprocated and reinforced over and over. So it is with the intellect. When I learn something you have shared with me, it does not pass from you to me like milk from a pitcher; you have lost nothing, and yet I have gained something that is now common to us both. The sum of what is common to us has just grown; it has not been redistributed. And should we together go about learning something new, we will each be richer for what we come to have in common.

Why, though, do we say that these ‘things in common’ belong to ‘friends’? I think it must have something to do with the reason we seek these common things. We are moved to love something because it is beautiful, or to love some person because he or she is beautiful to us. We seek to know something because we believe that knowing is better than not knowing, that this knowledge will be good for us, perhaps even that it can be turned to good in the world about us. These things we have in common are beautiful and good things, and we wish beautiful and good things for our friends. If the common goods are those that increase by pursuing them together, then the greatest acts of friendship must be the searching together for such a common good.

St. John’s College exists for this purpose: to provide a place and countless opportunities for our students to pursue together the common goods of the intellect. We call ourselves a community of learning, aware that the word ‘community’ in English, as in Greek, has the same root as the word ‘common’. We make many an effort to put into practice the conviction that we learn best when we learn with others, who like us, wish to increase the common good. Such a community offers some pretty fine opportunities for friendship.

We also have a common curriculum that has us all reading books that are worthy of our attention, even of our love — books written by men and women who were themselves model fellow learners. The books and the authors may even become our friends, as can the characters in some of those books. If you have not already met the Socrates of Plato’s dialogues, you soon will, and you will be spending a lot of time with him in your freshman year. For some of you, this may be the beginning of a lifelong friendship with a character who would converse with you over and over if you open yourselves to the possibility. The words on the page may remain the same, but the reader brings a new conversationalist to the text every time he or she returns to the dialogue. At least, so it is with me. I call Socrates a friend of mine because I know that he seeks only my own good. He has taught me humility, at least such as I possess it at all.

I have many such friends in the Program. Some of them are books: Homer’s Iliad has been my companion since the seventh grade, and I never tire of returning to it. The Aeneid has become a more recent friend who has helped me understand and better bear the responsibilities of fatherhood and the trials of leadership. The Books of Genesis and Job have helped me understand what it means to be human and how great is the distance between the human and the divine; I read them to remind me of how little I really understand about the relation between the two, which in turn serves as a spur to seeking to understand better. Euclid’s Elements may be the finest example on the St. John’s Program of the practice of the liberal arts, and it is beautiful for its logical, progressive movement from the elemental to the truly grand. Plato’s Republic is the finest book about education ever written; it inspires much of what I do as I practice my vocation at the College, reminding me that a community of learning is reshaping and refounding itself any time a few of its members come together to engage in learning for its own sake — and that this is what we ought always to be encouraging at this college, even by device when necessary.

Other friends of mine are authors: Sophocles, who can evoke a human sympathy to inspire pity in each of his dramas; George Washington, whose restraint in the use of power is evident in his finest writings and in the mark he left on the founding of this country; Abraham Lincoln, whom I consider this country’s finest poet, whose very words reshaped what it meant to be an American; Jane Austen, whose every sentence can be called perfect (and so she is a beautiful author to me); and Martin Luther King, who taught me that non-violent protest is more than a successful tactical measure to achieve a political end, but a proper and loving response to the hateful misconduct of fellow human souls.

Then there remain the characters whom I embrace as friends: besides Socrates, there is Hector, Breaker of Horses, ‘Oh my Warrior’; and Penelope, who weaves the path that allows Odysseus to return home and is far worthier of his love than he is of hers. There is Don Quixote, the indomitable spirit, and Middlemarch’s Dorothea Brooks, whose simple acts of goodness change the whole world about her. I rather like Milton’s Eve, mother of us all, who still shines pretty brightly in the face of his spectacular Satan. I was a teenager when I met Shakespeare’s Prince Hal, and I grew to adulthood with him, probably following a little too closely his path to responsibility. There’s the innocent Billy Budd, unprepared to face the force of evil in man, and his Captain Vere, the good man who suffers to do his duty.

You will also read some reflections on friendship: this winter, Aristotle will provide freshmen with a framework for considering different kinds of friendships and the goods they afford. You should ask whether you think his list is complete, and whether your own experiences of friendship are embraced by his explication. And then there are examples of friendships, pairs of friends, in many of the books, who will also provide lessons in friendship, for better or worse: Patroclus and Achilles, David and Jonathan, Hal and Falstaff, Huck and Jim, Emma and Knightly, to name a few.

As you work your way through the Program, you will have the assistance of many friends, some of whom will still be breathing while others will be living on in the pages you’ll be reading during your years with us. They will help you as you struggle with the big questions that in turn will help to free you to live a life that truly belongs to you. It will be these friends, who are outside of you but standing close by, who will help you find your own answers to the questions: Who am I? What is my place in the world? And how ought I to live my life? One of my more beautiful living friends, a colleague here at the college, has put it this way: “Our friends are doubly our benefactors: They take us out of ourselves and they help us to return, to face together with them our common human condition.” (Eva Brann, Open Secrets/Inward Prospects, at 55.)

Another of my friends, a St. John’s classmate and medical doctor, gave last year’s graduating class in Santa Fe this reminder, that we can learn from our friendships with the books how we might be better friends to one another. “It is the great book that is the life of every person, regardless of station in life,” he said. “So often we make shallow and inaccurate presumptions about people, like the cliché of telling a book by its cover, which robs you of the deeper experience that defines us as humans in our relationship to each other. For me every patient is a great book with a story to tell and much to teach me, and I am sometimes ashamed when my presumptions are exposed and I then see the remarkable person within, between the covers of the book of the story of their own lives.” This doctor has devoted himself to saving the lives of patients suffering from cancer, and he has this to say about how he is guided by the spirit of community and friendship within the soul of every human being: “In my own work, it is sometimes said, we are guided … by the idea that to save a person’s life, it is considered as if one has saved the world. To me that has always meant the life saved is much more than a single life restored, as that person is someone’s spouse, someone’s brother or sister, someone’s parent, or child, a member of a community, of a church, synagogue or mosque, or a friend, and as all are affected by loss, all are restored by their return.” (Stephen J. Forman, 2009 Commencement Address, Santa Fe) This statement is a powerful testament to the wonder of friendship at work in the world.

In this last story, I have moved us away from the inner world of reflection and learning to the outer world of putting what one has learned to work in a life devoted to helping others. The second must always follow the first. By this, I mean that you owe it to yourselves and others to take advantage of the opportunities this community offers you to learn with your classmates and tutors what it takes to acquire a little self-understanding before you go out and put it to work in the world. And in the process, we hope that you will make a few friends who will stay with you for the rest of your lives, enriching your lives because ‘what friends have, they have in common.’

I wish to close with a kind of benediction. This little nominal sentence Κοίνά τά τών φίλων happens to be the penultimate sentence in one of Plato’s dialogues, The Phaedrus, the only book you will read twice for seminar, at the end of both your freshman and senior years. Phaedrus and Socrates have engaged in the highest form of friendship as they have conversed together to try to understand how a man or woman might achieve harmony and balance in the soul by directing that soul to a love for the beautiful. Socrates concludes with this prayer to the gods:

Friend Pan and however many other gods are here, grant me to become beautiful in respect to the things within. And as to whatever things I have outside, grant that they be friendly to the things inside me. May I believe the wise man to be rich. May I have as big a mass of gold as no one other than the moderate man of sound mind could bear or bring along.

Do we still need something else, Phaedrus? For I think I’ve prayed in a measured fashion.

To which Phaedrus responds:

And pray also for these things for me. For friends’ things are in common.

(Plato, Phaedrus, Nichols translation, lines 279b-279c)

May each of you, as well, learn to enjoy the benefits of such friendships in your time at this College! (And now, in the concluding words of Socrates, “Let’s go” and get started.)

Convocation Address, August 26, 2009 by Christopher B. Nelson, President, St. John’s College, Annapolis MD. Published here by permission.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

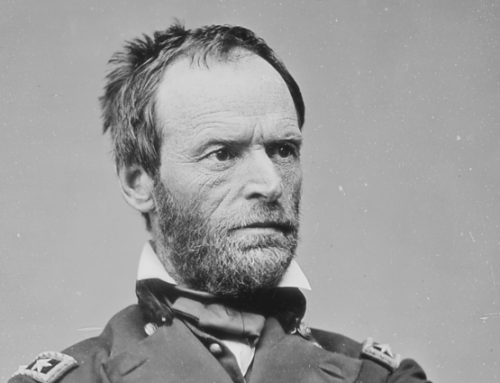

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay and has been brightened for clarity.

Leave A Comment