“Fortitude without justice is a source of evil.”—St. Thomas Aquinas

The great moralists tell us that a person’s strength is often the source of his greatest weakness, whether it is business acumen, artistic creativity, or physical excellence. Any of these things can be exercised too much or in the wrong way. The same is true of courage. A systematic analysis of this subject is provided by Thomistic philosopher Josef Pieper in his classic work The Four Cardinal Virtues (Ignatius Press). Pieper sums up the virtues in this way: “Prudence looks to all existent reality; justice to the fellow man; the man of fortitude relinquishes, in self-forgetfulness, his own possessions and life. Temperance… aims at each man himself.”

One of the best treatments of courage, and certainly the most famous, is Homer’s Iliad. When reading the epic poem there is no doubting the sheer audacity of the Achaeans besieging Troy, but at the same time these men represent a semi-barbarian warrior culture whose heroes are bent chiefly on plunder and revenge. Even the ancient Greek historian Herodotus argued that “the Greeks… were, in a military sense, the aggressors.” Centuries later the English Catholic poet Dryden put it more bluntly: “Science distinguishes a man of honour from one of those athletic brutes whom, undeservedly, we call heroes. Cursed be the poet, who first honoured with that name a mere Ajax, a man-killing idiot!”

For many readers, the most admirable champion of the Iliad is Hector rather than the superhuman Achilles. The former represents the domestic virtues of the settled and civilized culture of Troy, whereas Achilles and the Greeks are little more than marauding pirates. Only in the end does the ferocious Achilles relent somewhat as Priam, father of the fallen Hector, imparts to him a sense of decency and restraint in their shared grief over those slain in battle.

As Pieper explains, “Fortitude points to something prior.” It is a subordinate virtue. An example of this is Achilles’ chief failing—his petulant temper. It is the “wrath of Achilles Peleus’ son,” sung in the opening lines of the poem, which leads to so much disaster for the Greeks. At one point the god Apollo denounces the “abominable Achilles… who has no sense of decency, no mercy in his mind.” He lacks a healthy sense of shame and rages even against the “clay” of Hector’s dead body. By contrast, the Trojan Aineias in his duel with Achilles appears as a superior warrior for his laconic self-control. He chides Achilles for his incessant boastfulness, asking “why must we bandy curses like a couple of scolding wives?”

We notice that in less civilized cultures, or periods of social decay, self-control and graciousness fall into abeyance as rivalry outstrips other qualities. Warriors will boast of their prowess in an absurd and shameless manner. We have traditionally strict rules about the comportment of soldiers. This is not only to maintain proper morale and proficiency, it also reinforces their role as defenders of a free society—which is something that the mercenary or ideologically fanatical combatant cannot do. When these rules are not adhered to we have the Abu Ghraib scandal or the adolescent antics of Owen Honors, the recently disciplined captain of a nuclear aircraft carrier.

Daring is not necessarily commensurate with rectitude. British historian Max Hastings has often noted in his works that the Third Reich fielded one of the most capable fighting forces in modern times. The German soldier, man for man, outfought all of opponents on all fronts, losing chiefly to the overwhelming numbers of his enemies. Other armies throughout history have earned similar reputations: Alexander’s Macedonian phalanx, Ghengis Khan’s horsemen, and the partisans of Mao Tse-tung. These men could be brave, but chiefly in pursuit of glory, hatred or personal gain.

According to Pieper: “If the specific character of fortitude consists in suffering injuries in the battle for the realization of the good, then the brave man must first know what the good is, and he must be brave for the sake of the good.” Fortitude is not the first of the virtues. “For neither difficulty nor effort causes virtue, but the good alone.” Admittedly this is a strange concept to Americans, because we have always seen bravery as a premier virtue (implicitly encompassing all the others) as embodied in the careers of George Washington, Davy Crockett or Sergeant Alvin York. At the same time we treat Al-Qaeda suicide bomber Mohamed Atta as a “coward” because he disregarded the rules of engagement. In one sense such assumptions speak well of our culture. But strictly speaking, were the 9/11 bombers cowardly? What about the Japanese kamikaze in World War II? The popular definition of courage seems incomplete.

While Pieper notes that bravery “presupposes a healthy vitality, perhaps more than any other virtue” he adds that it “has nothing to do with a purely vital, blind, exuberant, daredevil spirit.” Referring to the paramount virtue of prudence, he warns that unreasoning fearlessness is based upon a “false appraisal and evaluation of reality.” In the case of the Viking berserker—chewing his shield and rushing half naked and screaming into battle—it can be foolishly blind to real danger. But there are other, more subtle dangers. Through a perversion of love, it can happen when a person values a “cause” more than his proper duty to himself or his neighbor. Finally it can happen when men allow themselves to be forced into evil through fear.

Pieper says that while one should avoid the noncommittal optimism of people who want good things without making sacrifices, “there is the equally pernicious easy enthusiasm which never wearies of proclaiming its ‘joyful readiness for martyrdom.’” The German philosopher invokes the example of St. Polycarp who admonished Christians not to presume on their own strength. Martyrdom was something God called us to, it was not something we should actively seek in an imprudent and hasty manner, especially since our courage might fail us at the last moment, thus setting an even worse example than if we had persevered quietly in whatever trials Providence may send us.

There is something wrong with such acts of reckless courage; not only in their methods but also their ends. In a world that has increasingly lost its spiritual moorings, bored or alienated souls may react to the inanity of mainstream materialism by embracing the shallow romanticism of extreme behavior. Theodore Dalrymple writes that “Danger absolves one of the need to deal with a hundred quotidian problems or to make a thousand little choices, each one [seemingly] unimportant. Danger simplifies existence and therefore—again when chosen, not imposed—comes as a relief from many anxieties.”

That can explain why individuals who perform so well in combat are sometimes aimless or dysfunctional in peacetime. In Dalrymple’s example, however, the stimulating love of danger and the distraction of superficially intense activity refers not to soldiering at all, but to youthful radicals, thrill-seekers, and the short-sighted and self-destructive behavior of many members of the perpetually unemployed. By contrast, Pieper reminds us that “the essence of fortitude is neither attack nor self-confidence nor wrath, but endurance and patience. Not because (and this cannot be sufficiently stressed) patience and endurance are in themselves better and more perfect than attack and self-confidence, but because, in the world as it is constituted, it is only in the supreme test, which leaves no other possibility of resistance than endurance, that the inmost and deepest strength of man reveals itself.”

To summarize, fortitude must be informed by foresight which determines what choices we make, according to a wise assessment of the world around us. This is not an excuse for irresolution. A person well practiced in the ways of good judgment should be all the more capable of making snap decisions when the situation demands it, because fortitude has become inclination based on virtue (or good habits). Secondly, courage demands justice. In our actions, especially those which involve radical choices and the potential for great harm as well as great good, it is crucial that we assess what is due to others as well as what is permitted to ourselves.

Books by Josef Pieper mentioned in this essay may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore. His most recent article is “On Gratitude & Growing Up,” (New Oxford Review, April 2012), a commentary on Dickens’ novel Great Expectations.

What you say is reasonable enough. Yet I believe that, more fundamentally, the primary use of courage (andreia = manliness) is to be directed towards oneself. It is to bravely confront and conquer those intellectual vices which make one cling to false opinion. It is the power that overcomes intellectual laziness (rhathymia), complacency and that conceit of knowledge which is truly the root of all evil. The Iliad, as the Neoplatonist commentators inform us, is an allegory: the Trojans are our inner weaknesses, our 'effeminate' attachments to pleasure, which corrupt our Reason, just as Paris' fall was his attachment to Helen's physical beauty.

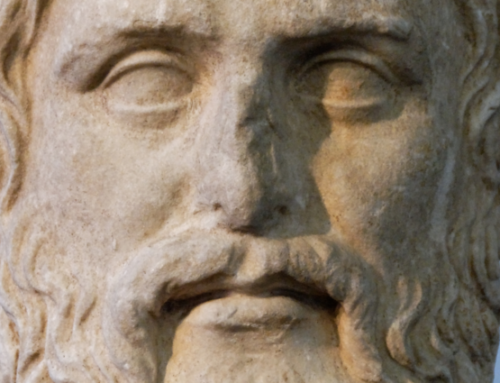

The courageous conservative is not one who rails against the atheism of our times or prevalent moral failings in society, but the one who has the courage to pull out a difficult and challenging book — Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, Origen — and to read it carefully and thoughtfully, catching oneself in the act of resisting or distorting the true meaning to suit ones fancies, and then pushing past the laziness, sacrificing comfort to truth.

Should anyone be interested, I've dedicated a web page to the andreia here:

http://www.john-uebersax.com/plato/words/andreia.htm